El Calafate and Glaciers

After our hiking in El Chalten, we headed to the charming village of El Calafate. The main reason for coming here is access to Los Glaciares National Park and Perito Moreno specifically. This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and covers 600,000 hectares (and no, I don’t know exactly how big a hectare is. I just read that in the informational pamphlet we got on the bus). Suffice it to say it’s big and contains the third-largest ice field in the word, after Antarctica and Greenland.

A sharp precipitation dropoff occurs east of the Andes because of the rain-shadow effect produced by the mountains. That means that while there are glaciers (essentially rivers of ice), the area does not get extremely cold, nor do they get much snow. They do, however, have several different habitats, including cold, upland meadows and woods where three species of trees grow. The driest habitat is the steppe, where plants adapt to the extremely dry conditions and very strong winds.

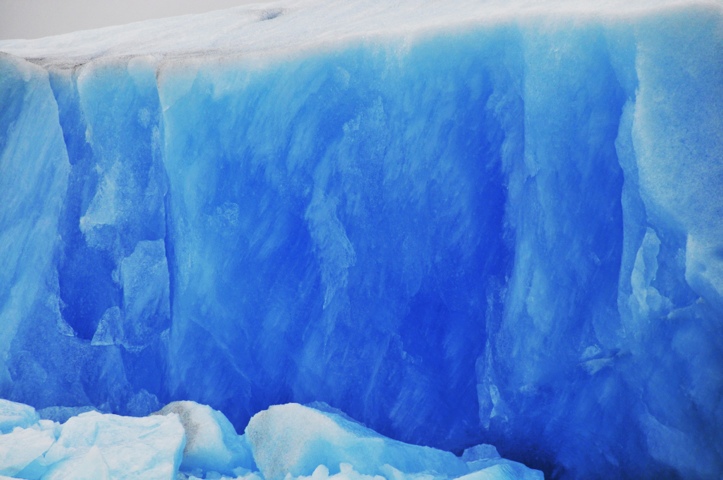

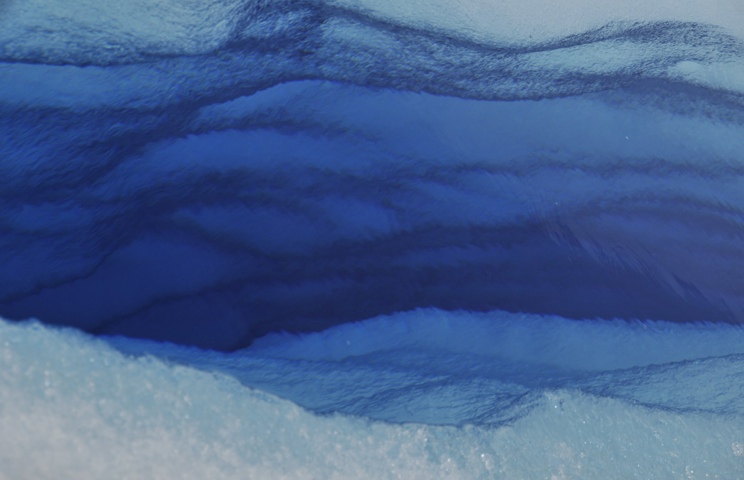

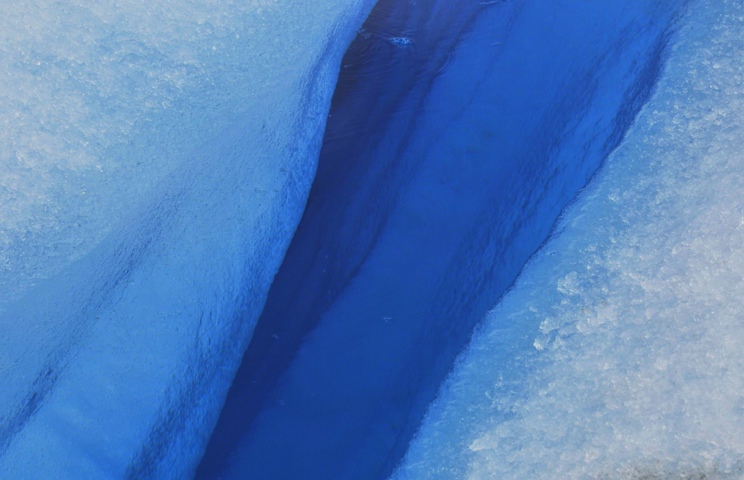

A few thousand years ago, glaciers covered most of the entire area of the Park. A glacier is essentially a very, very slow-moving river of ice. To give you an idea, the fastest glacier in the park, Uppsala, travels twelve meters a day, and Perito Moreno only two. A glacier is formed when layers and layers of snow are compacted to the point that they become ice. (The darker the blue color, the less oxygen and more dense the ice is.)

More snow falls on top of the ice, but all of the snow and ice retain the general shape of the land underneath it, hence the rises and falls on the surface of the glacier. Under all this pressure, the ice actually flows. When it reaches the lake (Lake Argentina, in the case of Perito Moreno), the face is easily over 100 feet tall. The glacier creaks and moans before ejecting parts of itself to the cold waters below. Because the size and location of these dislodged shards is unpredictable, boats must remain a safe distance from the face.

When the glaciers advanced, they eroded the land, creating steep valleys and depositing this material at the ends (and as they retreated, also to the sides). With the warming climate, the ice has retreated to the mountain areas where we see it today, and the valleys’ huge lakes are now much smaller in size. The water gets its turquoise color because it holds minute powdered particles in suspension.

One Day One, we took a daylong boat cruise to the faces of five glaciers, including Perito Moreno. The piercing white of the snow was tamed by hints of blue, at times in rich, deep hues. It was amazing to see those big walls of ice – and even more so to hear the creaking and try to predict where the pieces would crash. The glaciers look like a freeze-framed river, and if you hit the play button, you’d set a huge rush of raging rapids down the mountainside.

Our other El Calafate adventure was a day of The Big Ice. After observing Perito Moreno from the observation decks, we took a boat to the side of its face and hiked about 45 minutes to reach the stable part of the glacier. At this point, it was time to strap on our crampons. If you’ve never hiked with crampons, it’s a must. Crampons make you feel like Captain Badass. They fit onto your boots and have triangle-shaped metal spikes that dig in to the ice. You can march around on the snow and ice like you own the place. I first used them in New Zealand, and they’ve had my undying admiration ever since.

The landscape of the ice matched the topography of the earth and stone far below it, with folds, rolling hills, and slight bumps everywhere. By the time we hit the ice, the sun started peeking out, and the temperature warmed quite a bit. We peeled layers as we walked, and by mid-afternoon, we were down to a single long-sleeved shirt.

Walter was our main guide, and he was far, far handsomer than the name Walter usually suggests. No offense to the Walters out there, but the name does not typically appear in the same context with a chiseled, blue-eyed, Argentine mountain man. Walter kept the group together and led us along quite a stretch of the glacial bed, explaining the glacier’s formation and other information. He also told me about some of his climbs and showed me the mountains in the distance that he hoped to summit one day.

Toto was Walter’s compadre. His job was to go ahead to help steer the path and axe steps into the steep parts. He’d run across the ice, whizzing by us as if he were skipping across a backyard. He also assisted during the more dicey bits, like when I was straddle-crossing a very deep crevasse and psyched myself out. There’s nothing like looking down into a deep abyss between your legs, with twenty feet to go before you can put your legs back together to incite terror about becoming a cliche, made-for-TV movie. Toto jumped down in front of me, took both my hands in his and guided me by walking backward, having me look at him while he sang to me. He is, without a doubt, my hero.

A trip to Patagonia should be high on anyone’s list if you like to hike and/or just to see some incredibly gorgeous sites. We were reluctant to swap this gorgeous natural area for the heat and hustle and bustle of Buenos Aires, but alas, it was time for us to go.